A Living Text.

-

AMiA Collapse 12

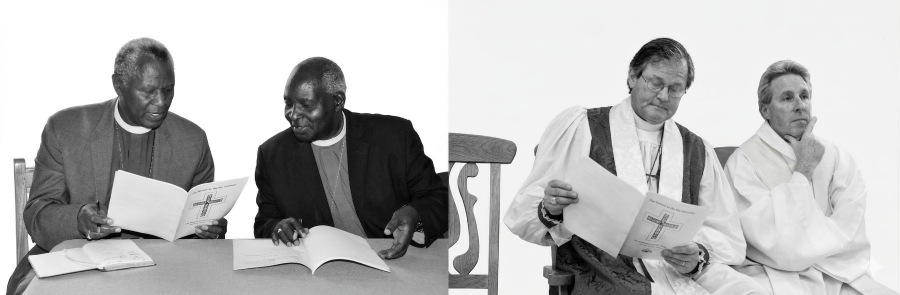

Speaking to All Saints Church in Pawleys Island in 2012, AMiA Bishop T.J. Johnston said, “The unfortunate thing is the leaders who profoundly led All Saints—Thad, Chuck, Shuler, name them all. You know what. They ain’t doing too well relationally.” The fissures between Terrell Glenn and Chuck Murphy led Glenn to resign in late 2011.…

-

AMiA Collapse 11

For months Bishop Terrell Glenn and his wife Teresa agonized in prayer about what to do about his leadership position within the AMiA. He had personal issues with Bishop Murphy that he could not resolve and many of his clergy–notably the D.C. authors of the Washington Statement–were unhappy with where things were headed. Apparently there…

-

AMiA Collapse 10

Writing in 2015, Bishop Terrell Glenn talked about the times of chaos that engulfed the AMiA. He said, “What followed was a season of enmity, demonization, and slander. Sides were chosen. False accusations were made. In one case, bishops turned on congregations and clergy in ways that were worse than anything that had occurred at…

-

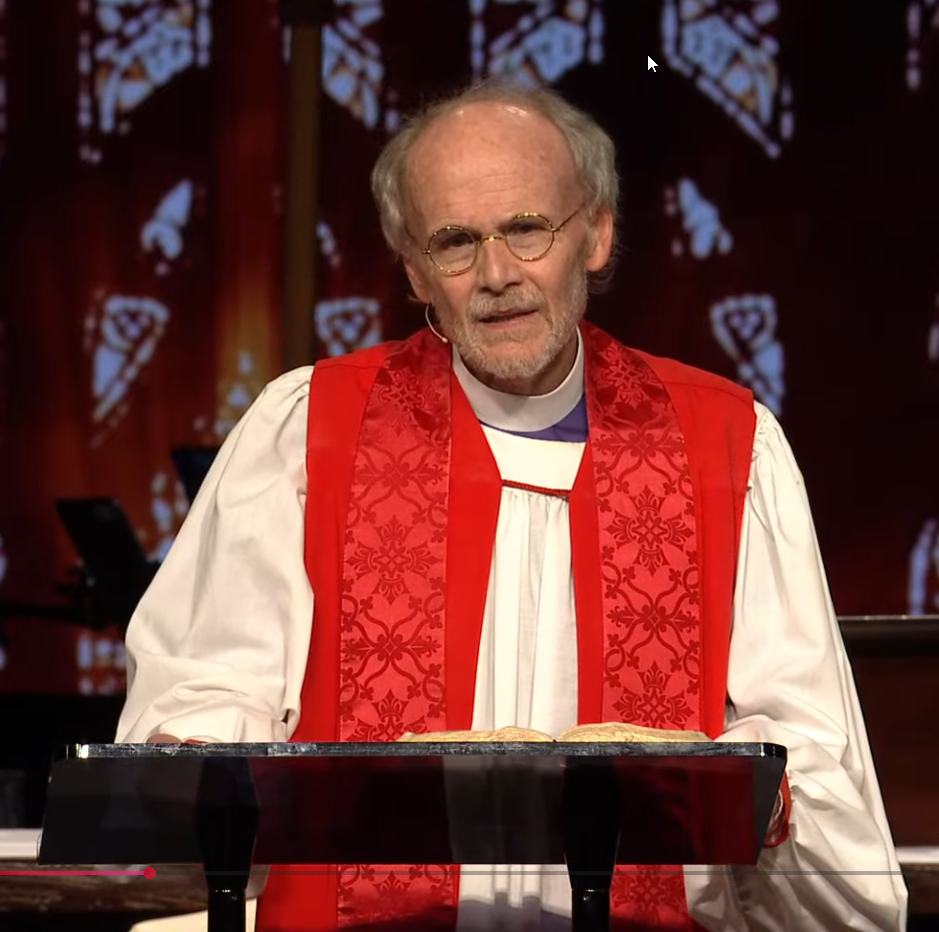

Bishop Thad Barnum blames the wrong people

Recently Bishop Thad Barnum preached at the consecration of The Rev. Canon Billy Waters, Suffragan Bishop Elect of the Anglican Diocese of the Rocky Mountains. Barnum is a fiery preacher and has a clear passion to preach the Gospel to the lost. I have witnessed him in person and it reminded me of what it…

-

When will ACNA bishops apologize?

ACNA’s catechism has this to say about the Ninth Commandment: What is bearing false witness against your neighbor?It is to willfully communicate a falsehood about my neighbor, either in legal or in other matters, in order to misrepresent them. Why does God forbid such false witness?Because it defames and wounds my neighbor, erodes my love…

-

AMiA Collapse 9

John Rucyahana’s October 25th letter provoked a response from another AMiA founding father, retired Archbishop Moses Tay of Singapore. Tay emailed Rucyahana on October 27, “…saying that he believed it to be clear that a spirit of rebellion and lawlessness was at work – beyond and beneath legitimate human concerns, procedures, and rationalizations. He then…

-

AMiA Collapse 8

Sometime around the Presbyter’s Retreat in Pawley’s Island there was a similar meeting of AMiA clergy in Little Rock where Bishop Murphy again presented the Mission Society proposal. Responses to the Murphy/Donlon/Kolini proposals were immediate, suggesting constant communication between American clergy and Rwanda. I cannot prove it, but I strongly suspect Bishop Laurent Mbanda was…

-

AMiA Collapse 7

(Picking back up from part 6) AMiA leadership had met with the Rwandan House of Bishops in September 2011 and now they would begin to road test the new Missionary Society concept to the clergy in their churches. On October 25th there was a Presbyter’s Retreat in Pawley’s Island. My own clergy from Washington D.C.…

-

Change Coming to the ACNA’s Convocation of the West

The ACNA is a confusing confederation of tribes with a variety of governance structures and theological beliefs. One of these structures is the Convocation of the West. Its history is given here: The Diocese of the West was founded in 1998 as part of the Anglican Province of America (APA), a Continuing Anglican church in the Anglo-Catholic…

-

Bishop Stewart Ruch’s Actions in Light of the ACNA’s Ordinal

Where does the buck stop in the ACNA? Is anyone responsible for anything or do clergy get to say, “mistakes were made” and leave a trail of destruction in their wake? The ACNA has a Constitution, and in Article I, Declaration 6 says: We receive The Book of Common Prayer as set forth by the…