(Continuing a series of posts on recent Anglican history.)

At the dawn of the twenty-first century the Anglican Communion experienced a profound rupture over issues of fidelity to Scripture. National churches from “the Global South” ordained Americans as missionary bishops to the United States, touching off a new level of spiritual warfare that pitted church against church and wreaked havoc on the traditional ecclesiastical arrangements within the Anglican Communion. The first organization that benefited from this realignment was called the Anglican Mission in America (AMiA), which descended from a previous organization called First Promise.

First Promise began in 1998 when a newly elected Rwandan Anglican bishop named John Rucyahana took American priest T.J. Johnston under his supervision – an innovative move at that time. Miranda Hassett recounts this episode:

The African bishop who took on the responsibility of protecting and overseeing Johnston was John Rucyahana, then newly elected bishop of the Diocese of Shyira in northwestern Rwanda. Rucyahana was well connected with American conservatives owing to his studies at Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry. He had met Johnston at the Dallas conference, and when Johnston found himself on ecclesiastical thin ice only months later, he appealed to Rucyahana. Johnston’s American bishop, the conservative-leaning Ed Salmon of South Carolina, agreed to transfer Johnston’s letters dismissory to Bishop Rucyahana–the official means of moving a priest to another bishop’s jurisdiction (Hassett 2007).

Lambeth 98

First Promise drafted a Statement of Purpose that outlined the departure of the Episcopal Church from Scriptural authority and proposed either reforming the Church or creating a new Province:

Whereas Christians are commanded by Jesus Christ in the Great Commission, Matt. 28:19-20, to “make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you…” and, Whereas the present leadership in the Episcopal Church is no longer committed to obeying or upholding these commandments and/or the authority of Holy Scripture, Therefore, the First Promise movement adopts the following purpose statement in an effort to bring this Episcopal Church back to its scriptural and apostolic roots and into conformity with the mind of the Anglican Communion as expressed in Lambeth 1998, and, To ensure that there always remains in the United States of America a church which is a constituent member of the Anglican Communion, and to take immediate and prudent steps to prepare and make available the necessary structures for an orthodox Anglican Province in the United States by either the reformation of the Episcopal Church or by the emergence of an alternative. – Approved 21 September, 1998 – Annual Meeting – Little Rock, Arkansas[1]

Alliances in the 90s

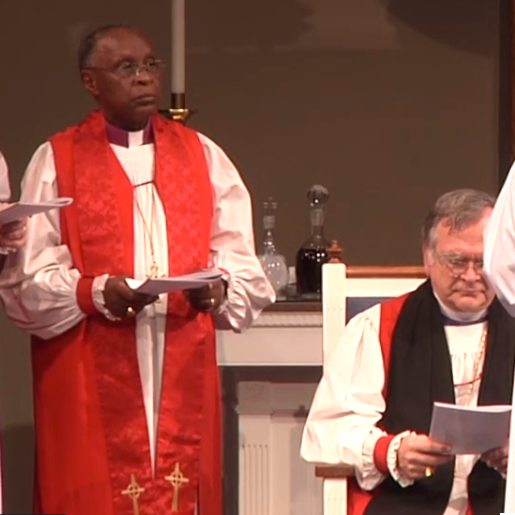

On January 29, 2000 Chuck Murphy and John Rodgers were consecrated as bishops in Singapore by a group of bishops consisting of FitzSimons Allison, Alex D. Dickson, Emmanuel Kolini, Moses Tay, David Pytches and John Rucyahana. The Anglican Mission in America was effectively born on that day.

The model that AMiA would trumpet of “churches that plant churches” was not original to Chuck Murphy. In fact, Episcopal priest Jon Shuler had founded the North American Missionary Society (NAMS) in 1994 and not coincidentally, it was headquartered in Pawley’s Island, South Carolina, the future headquarters of AMIA. See the post on Jun Shuler for details.

The North American Missionary Society (NAMS) is up and running, seeking to fulfill its mission to “develop and plant great commission churches within the Episcopal Church and in the Anglican tradition, which will themselves plant great commission churches, and to work in alliance with existing congregations and others who share this vision.”

Three initial training and networking conferences were held recently in Pawleys Island, S.C., where NAMS is headquartered. More than 90 conference participants learned and exchanged information about church planting and congregational development.

“There will be a certain character to a NAMS church,” said the Rev. Jon Shuler, general secretary of NAMS. “Our focus is the planting of new churches that will plant other churches, who will make disciples who will go and make disciples.”[2]

Further, an article about the beginning of NAMS said: “The goal is not to attract members from those churches, but to reach out with evangelistic compassion to growing ranks of unchurched Americans.” This sentence would be repeated in an almost mantra like fashion over the next two decades by AMiA, the Anglican Church in North America and other groups that made up the realignment.

According to Ross Lindsay:

In 1994, the Rev. Jon Shuler, a TEC priest in Knoxville, Tennessee and the General Secretary of the North American Missionary Society (NAMS) asked Chuck Murphy, the rector of All Saints Church in Pawleys Island, if he and his parish would become a partner in NAMS. […] Two years later, Jon Shuler moved the headquarters of NAMS onto the campus of All Saints Church and along with him came a young priest named Thaddeus Barnum.

Thaddeus Barnum, a graduate of Yale Divinity School, had served under Terry Fullam at St. Paul’s, Darien before he and his wife, Erilynne, left Connecticut to plant a new church outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In his book, Never Silent, Barnum tells the story of how he met John Rucyahana, an African priest who was studying at Trinity School for Ministry in Pittsburgh. Soon thereafter, Thad and Erilynne became affiliated with NAMS, and they moved to Pawleys Island were Thad joined the staff of All Saints Church.

Jon Shuler, Thad Barnum, and Jon Rucyahana are the unsung heroes of the Breakaway Anglican Church Movement. But for NAMS and Thad Barnum’s relationship with John Rucyahana, the Singapore Consecrations may not have occurred. [3]

The twist that the AMiA supplied to the re-evangelization narrative was that this effort was ostensibly led by the Rwandans. AMiA Anglicans could tout themselves as “Rwandan missionaries” to America, although this was playing a bit loose with the facts. [4]

However, Jon Shuler and Chuck Murphy were hardly the only game in town when it came to the realignment. Bob Duncan, Martyn Minns, and Ray Sutton (among others) had their own versions of how the future would play out.

Bishop Sutton’s Ugandan Connections

While at Cranmer Theological House, Bishop Sutton began establishing relationships with Anglicans in Uganda, at the same time his counterparts were working with Rwanda and other African nations in what would become the pattern for the Anglican realignment. First, In March, 1999 Ugandans participated in the ordination of two deacons. David Virtue reported on the event:

In the chapel attached to the small seminary of the Reformed Episcopal Church in Shreveport, LA, a remarkable event took place on Wednesday, March 24 between 10.30 am and 12:15 p.m.

The Right Rev’d Terence Kelshaw of the Episcopal Diocese of the Rio Grande and the Bishop of the local Reformed Episcopal Church diocese, the Right Revd Royal Grote jointly ordained two young men as deacons…The two candidates were presented by the multi-millionaire owner of the factory to which the seminary and chapel are attached, Allen Dickson, and by the dean of the Seminary, Ray Sutton. They explained that these men were being ordained for the Bishop of Namirembe (Uganda) whose name is Samuel Balagadde Ssekaddee but that they would serve in the Episcopal Diocese of the Rio Grande under Kelshaw rather than in Uganda…At the ordination the ordination prayer was said by both bishops together for each man and both bishops laid their hands upon each one. The ordination certificate with Kelshaw’s seal on it also had on it the name of the Ugandan bishop.

The Communion Service was from the 1928 BCP and the celebrant was the Reformed Episcopal Bishop, Royal Grote. Not more than 40 or so were present, most of them from the seminary and factory.

By this device the seminary placed two of its students and St. Francis parish got two assistants and the Bishop of the Rio Grande circumvented the normal procedures for ordination of dioceses in the ECUSA. Further, the Ugandan bishop has two of his deacons as missionaries in a foreign land.

On August 3rd of that same year, in what a source called “the high water mark of the seminary,” Sutton was consecrated as Bishop, and a delegation of Ugandans was present at the consecration. The idea going in was the Ugandans would ordain Sutton (this was prior to the rupture that the AMiA consecrations produced), but things did not proceed according to plan. A source close to the events says:

Dickson, always looking for an opportunity, flew in six Ugandan bishops to take part in the consecration, and invited every “conservative” bishop in TEC as well. Of course, none of the TEC bishops showed up, save one, but not for the consecration itself. Bp. Stanton of Dallas appeared the day before the consecration to persuade his good friend, Bp. Sekkade, to NOT take part in the consecration, because this would essentially legitimize RE orders (if not confer valid Anglican orders)…After a five minute conversation, the Ugandan bishops agreed not to take an active role (lay hands) in the consecration itself, but would simply pray for the newly consecrated bishop. One Ugandan bishop confided…that he hadn’t realized until Bishop Stanton showed up that the Reformed Episcopal Church was actually different from The Episcopal Church.

Robert Harwell reported on the event and the news was distributed by David Virtue:

Anglicans in Africa and the United States moved closer together this week when a delegation from the House of Bishops of the Ugandan Anglican Church traveled to Shreveport, Louisiana. The six Ugandan bishops were visiting Cranmer Theological House, a seminary of the Reformed Episcopal Church. The Episcopal Church USA is not in communion with the Reformed Episcopal Church, nor has it extended accreditation to Cranmer Theological House…

While in Shreveport the Ugandan bishops attended the Consecration of the Rt. Rev. Ray R. Sutton, dean of Cranmer. In the consecration ceremonies that took place at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, the Ugandan visitors participation was restrained. They took no part in Sutton’s Consecration by Reformed Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop, the Rt. Rev. Leonard Wayne Riches and other bishops of the Reformed Episcopal Church.

In what would become a familiar story in the next century, the African connection was emphasized:

In conversation after the ceremonies, Dean Sutton revealed that, in addition to the two Ugandan students arriving in early August, two others would “soon” be enrolling in Cranmer. He stated that the six Ugandan bishops were on a “fact-finding” mission, gathering first-hand impressions of Cranmer Theological House and the Reformed Episcopal Church. The six will report on Cranmer and the Reformed Episcopal Church to the Ugandan House of Bishops which they represent.

The hope was that Cranmer Theological House would have a wide-ranging influence on the Episcopalian sphere inside the USA, something that never materialized:

Dean Sutton characterized happenings at Cranmer House as “revealing ourselves to a larger Christian audience and to the world.” Pleased with current developments, he obviously believes that situations of real significance lie ahead for Cranmer Theological House.

It seems that Bishop Sutton had the same general idea that future bishops Chuck Murphy and Martyn Minns would have: a new organization within America that might be the basis of a future Province. A source put it this way:

Essentially, the Dickson/Sutton plan was devised to give the REC legitimacy as an American Anglican province outside of TEC jurisdiction and CTH legitimacy as an Anglican seminary. Ray was more than just a willing player. Before all of this took place, he was quite candid…about what his consecration would mean for the “future of Anglicanism” as we know it.

[1]First Promise – Statement of Purpose.

[2]The Living Church April 30, 1995 Missionary Society Moving Ahead by John R. Throop, 210(18) p. 6.

[3] Ross Lindsay, Out of Africa: The Breakaway Anglican Churches, Xulon Press, 2011, p. 35.

[4] “Through AMiA, Claire became a Rwandan missionary to Washington, D.C., and started the Church of the Resurrection on Capitol Hill.” (http://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/to-renew-d-c-church-planting-in-the-nations-capital)