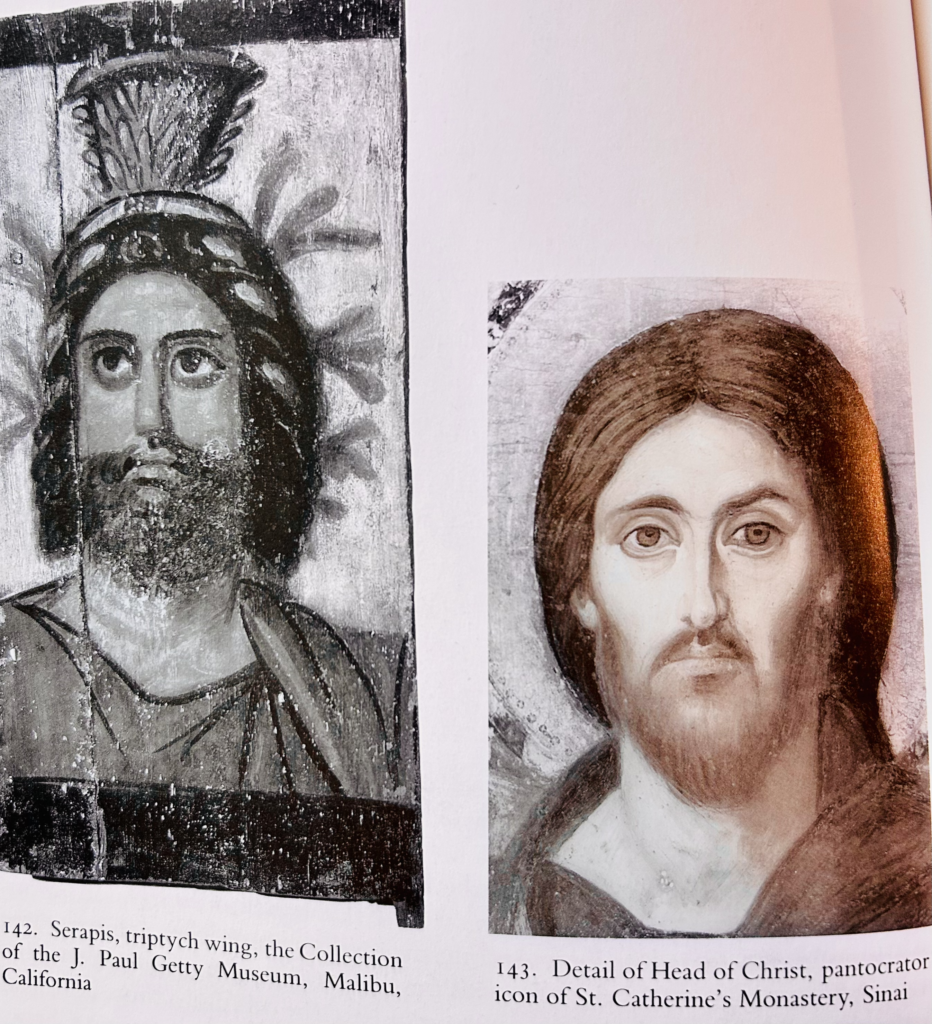

Serapis transformed into Christ.

For we did not follow cunningly devised fables when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but were eyewitnesses of His majesty.

2 Peter 1:16

John Roop, Anglican Diocese of the South canon theologian and priest at Apostles Anglican Church in Knoxville, wrote a post that delves into the field of historiography. Roop responded to my post about image worship with his own definitions of history. Roop posits that there is:

- Objective history: an oxymoron that “implies an independent, unbiased observer who in no way interacts with what is being observed or reported.”

- Subjective history: What every historian does. Includes selecting some facts to include and some to omit. He selects some subjects to interview and others to ignore. How history is actually and inevitably done.

- Tradition or sacred myth: sometimes factual and sometimes not.

I would look to another Anglican for sharper definitions. N.T. Wright provides a masterful definition of critical realism and history in his The New Testament and the People of God, where he says that “history…is neither ‘bare facts’ nor ‘subjective interpretations’, but is rather the meaningful narrative of events and intentions” (82). Wright goes on to outline the Enlightenment view of access to events unmediated by an observer–something similar to the view that Roop calls “objective history.” Wright helpfully points out that the ancients “…knew as well as we do that there are such things as actual events, and that it is the business of the historian to write about them, discounting ones which he thinks incredible” (84). Wright also points out that the quest for objectivity is hardly an Enlightenment invention, noting that Tacitus wrote “I shall write without indignation or partisanship” (85). Looking at the father of history, Raymond Kierstead writes, “Herodotus sought to separate fact from myth, to query his sources, to get the story right. In so doing, Herodotus established what would be the fundamental framework and subject matter of this new form of inquiry.” Thus far, we agree: ancients were not utterly blinded to attempting to be impartial and moderns who believe in unmediated access to events are themselves deluded.

Wright goes on to say that the way history is written does not mean that there “are no such things as ‘facts’ “ (88). Critical realism understands that “There are such things as events in the external world” (90). “We are looking at events” (90). This means that not “…all angles of looking at events are equally valid or proper” (91).

Wright proposes a system of hypothesis and verification to construct history. He says this system must:

- Include the data.

- Construct a basically simple and coherent overall picture.

- Prove itself fruitful in other related areas or help to explain other problems.

Wright points out that the opposite side of positivism is phenomenalism, solipsism, and fundamentalism, “…the closed mind…that cannot bear the thought of a new, or revised, story” (103). Wright then puts forward a definition of history:

History, then, is real knowledge, of a particular sort. It is arrived at, like all knowledge, by the spiral of epistemology, in which the story-telling human community launches enquiries, forms provisional judgements about which stories are likely to be successful in answering those enquiries, and then tests these judgements by further interaction with data (109).

We can see that the choice is not a false one between “objective history” and some sort of subjective story that does not verify facts. History can contain parables, but a parable is not history. To compare parables Jesus told to imaginary stories put forward as history is to make a false comparison. This can be easily seen by comparing the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Both texts tell tales of ancient Judah, of prophets and of patriarchs, but the Book of Mormon adds details about Jewish prophets who sailed across the ocean to the Americas and founded a civilization that is eventually visited by a resurrected Jesus Christ. Is this sacred American myth historical? Is it good for the soul? Many modern Latter-Day Saint apologists have essentially abandoned defending the historicity of the texts and instead focus on feelings and how these stories work for them, regardless of whether any of the stories are factual.

Obviously, we must reject such an approach as Christians. Peter makes a point of telling his readers that he did not follow “cleverly devised fables” but that he and others were eyewitnesses of Jesus. With this in mind, we must be grateful for Calvin and others who cared for their parishioners so much that they would not teach them nonsense without regard for eternal consequences. Calvin as a Christian humanist was practicing critical history of the sort which N.T. Wright would recognize. He details the pieces of “the true cross” circulating in his day and says:

Now let us consider how many relics of the true cross there are in the world. An account of those merely with which I am acquainted would fill a whole volume, for there is not a church, from a cathedral to the most miserable abbey or parish church, that does not contain a piece. Large splinters of it are preserved in various places, as for instance in the Holy Chapel at Paris, whilst at Rome they show a crucifix of considerable size made entirely, they say, from this wood. In short, if we were to collect all these pieces of the true cross exhibited in various parts, they would form a whole ship’s cargo.

The Gospel testifies that the cross could be borne by one single individual; how glaring, then, is the audacity now to pretend to display more relics of wood than three hundred men could carry! As an explanation of this, they have invented the tale, that whatever quantity of wood may be cut off this true cross, its size never decreases. This is, however, such a clumsy and silly imposture, that the most superstitious may see through it. The most absurd stories are also told respecting the manner in which various pieces of the cross were conveyed to the places where they are now shown; thus, for instance, we are informed that they were brought by angels, or had fallen from heaven. By these means they seduce ignorant people into idolatry, for they are not satisfied with deceiving the credulous, by affirming that pieces of common wood are portions of the true cross, but they pretend that it should be worshiped, which is a diabolical doctrine, expressly reproved by St Ambrose as a Pagan superstition.

In our day we have a much better picture of the origins of the story of Helena. Jan Willem Drijvers in his book Cyril of Jerusalem: Bishop and City writes of the story:

The first testimony for that is Ambrose of Milan’s funeral oration for the emperor Theodosius I of 395 in which the story is included (167).

A similar story, although without any mention of Helena, is presented by John Chrysostom in a homily at about the same time as Ambrose delivered his funeral oration in honor of Theodosius. However, such a story apparently did not yet exist by the time Cyril wrote his Letter to Constantius and delivered his Catechetical Lectures, otherwise it is hardly imaginable that he would not have referred to it. It is therefore most probable that the story about the discovery of the Cross only arose in the second half of the fourth century. Recent research has made clear that Ambrose’s narrative about the inventio crucis was most probably a variant of an originally, now lost, Greek story (167-68).

Further:

This story, commonly referred to as the Helena legend, spread rapidly. It was included in the fifth-century Church Histories of Socrates, Sozomen and Theodoret and also knew other Latin renderings, besides that of Rufinus. Soon two other versions of the legend of the inventio crucis arose: the so-called Protonike legend and the Judas Kyriakos legend. The first was only known in Syriac (and later in Armenian); the story is pushed back to the first century c.e. and Helena is replaced as protagonist by the fictitious Protonike, wife of the emperor Claudius. In the Judas Kyriakos version, which is characterized by severe anti-judaism, the Jew Judas finds the Cross and nails for Helena, converts to Christianity and eventually becomes bishop of Jerusalem. Like Protonike, Judas is also a fictional character created for the sake of the legend. In Late Antiquity, the Byzantine period and the western Middle Ages the story of the legend of the discovery, in particular the Judas Kyriakos version, became very popular, and was known in many variants and in many also vernacular – languages. It also became a favorite subject in the visual arts.

Drijvers makes the case that Cyril the Bishop of Jerusalem was the probable source of the story for political reasons, seeking to align the See of Jerusalem with the Imperial House. He says that “Although testimony is not available, it seems therefore not improbable that Cyril was responsible for the origin and composition of the story of Helena’s inventio crucis” (173).

According to Drijvers:

The discovery of the Cross brought Helena great fame and is the accomplishment for which she is remembered by posterity and earned her sainthood. However, it is good to realize that the legend of Helena’s inventio crucis is a construct and not a historical source for the events it describes, let alone a reliable source. Hence, Helena acquired her fame for an act for which she was not responsible. It is not known exactly how and when the Cross, or pieces of wood alleged to be the Cross, was found in Jerusalem, but Helena had nothing to do with it, as most modern authors ascertain” (173).

He notes that some disagree and points us to their writings, but does not find them persuasive.

This is how good history is done. Presenting facts, stating a hypothesis and a conclusion, and being open to correction. It is not pretending to be “objective history” that has direct unmediated access to the facts. Contrast this with Roop’s conclusion: “I do not know if St. Helena found Calvary or the wood of three crosses, and I do not care. The story is important and true nonetheless.”

Who cares about the truth? Who said that in the Bible? Pilate, more or less. As Christians we are supremely concerned with truth. I don’t believe in the Donation of Constantine or that Luke painted Mary. Why? Because of historical evidence. It is tremendously freeing as a Christian to know that we are responsible to obey what God has breathed in Scripture, and not anything else, whatever tradition or story it rests on. Who trumpeted traditions in the Bible? We all know the answer to that.

Leave a Reply