A Historical Sketch

A Text by Sir Robert Phillimore

[Updated and edited]

The following post is excerpted from a book published in the 19th century. In the book The Principal Ecclesiastical Judgments Delivered in the Court of Arches 1867 to 1875 by the Right Hon. Sir Robert Phillimore, D.C.L., there is an interesting case that reflects on images in the Church of England in the 19th century. The case was Boyd and Others vs. Phillpotts, and one conclusion of the case was:

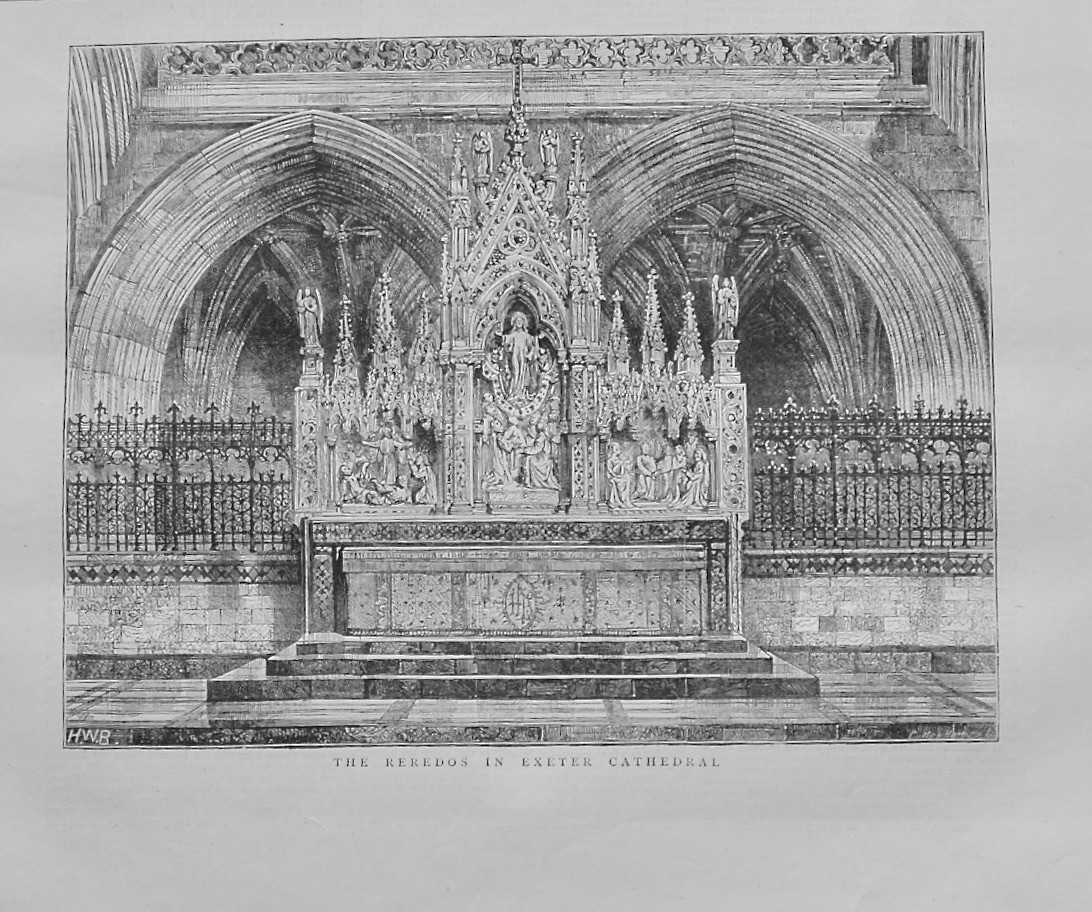

“A rerdos1 having on it sculptured representations in bas-relief of historical scenes taken from the New Testament, and surmounted by a cross and figures of angles, is not unlawful.”

The particular rerdos in question contained three scenes, “The Ascension of our Blessed Lord, the Transfiguration of our Blessed Lord, and the Descent of the Holy Ghost on the Day of Pentecost. There is an angel at each side of the rerdos, and two other angels, one on each side of the cross which surmounts the rerdos.”

The Bishop ordered this structure (the reredos) to be removed, and “either a stone screen without images thereon to be erected, or an open ironwork lately erected and now standing on each side of the reredos to be continued so as to occupy its place,” and the Ten Commandments to be set up at the east end of the choir of the cathedral.

Surely, apart from all legal considerations, it would be difficult to conceive a series of representations more likely to edify and instruct the spectators in Christianity, and less obnoxious to the charge of superstition than those which have been just described. Nevertheless, if such representations be prohibited by the law of the English Church, that law must be enforced by this Court.

In Mr. Phillpotts argument, images have been objected to on various grounds; the principal were, I think, the following:

- That they were contrary to the usage and practice of the pure and primitive Church;

- That they were objects of special censure by those who conducted the Reformation in England;

- That they were ordered to be moved out of churches by various authorities having the force of law;

- That there is a specific statute which renders them illegal;

That if it is a matter of discretion whether they shall be allowed to remain or not, that discretion ought to be exercised in favor of this removal, inasmuch as they tend to idolatry, forbidden by the Second Commandment, and to superstitions favored by the Church of Rome and rejected by the Church of England.

An anxious care to avoid the idolatry of the Jews and the Gentiles was no doubt the reason why, in the earliest Christian history, the Acts of the Apostles, we find St. Stephen applying the words of the prophet Amos to the Israelites, and rebuking them “for the figures which ye made to worship them,” – (Acts of the Apostles, 7.43).

During the first three centuries, images in churches were very rare, if they existed at all. Fleury, indeed, states, upon the authority of Tertullian, that there were images in some churches, and upon the vessels used in divine worship.2 The warning of St. John (1 John 5.21) against idols related to the sacrifices offered by the heathen to their idols, from which Christians were admonished to abstain. But the New Testament being silent on the subject of images generally, the moral text of the Second Commandment appears to have been considered binding upon Christians. And Tertullian, in his answer to the Marcionites, observes that the Jews were not prohibited from having images unless they worshiped them, and that therefore there was no contradiction between the Second Commandment and the cherubim ordained for the ark, or the brazen serpent.3 The words of Tertullian are: “So also the cherubim and seraphim of gold, for that figurative prototype the ark, were certainly a mere adornment, being designed to enhance its dignity. They had a purpose entirely opposite to that idolatrous propensity on account of which the making of a likeness is prohibited, and evidently are no infringement of the law which prohibits likenesses, for they are not convicted of being in that class of likeness on account of which a likeness is prohibited.”4

As the authority of the Second Commandment was a part of the argument addressed to me against the use of graven images in a church, it is not irrelevant to advert to the opinion of Bishop Taylor upon this point. Referring to the prohibition in the Second Commandment, he does not mention the two cherubim of gold in the ark, stretching forth their wings on high and their faces looking one to another, and toward the mercy seat (Exodus 15.20), or “the molten sea, and under it the similitude of the twelve oxen which did compass it about,” or “the two cherubim of image work overlaid with gold” (2 Chron. iii.10, iv. 2,3); but he observes: – “But when we consider further, that Solomon caused golden lions to be made about his throne, and the Jews imprinted images of Caesar on their coin, and found no reprover for so doing, this shows that there was something in the Commandment that was not moral; I mean the prohibition of making or having any images. For to these things we find no command of God, no dispensation, no allowance positive; but the immunity of reason, and the indemnity of not being reproved: and therefore, for so much as concerns the making or having of pictures and images, we are at liberty, without the warranty of an express commandment from God.”5

Some of the Fathers of the primitive church condemned the arts of painting and sculpture as in themselves wicked, and declared, as Jeremy Taylor says, that “God forbade the very trade in itself” (P.395). But he adds, “Now if this sense was also in the commandment, it is certain that this was but temporary; and therefore could change;” and he cites the instances of God’s assisting Bezaleel and Aholiab (p. 396).

“I conclude” (he says) “that the Second Commandment is a moral and natural precept in the whole body and constitution of it, if the first words of it be relative to the last; that is, if the prohibition of making images be understood so as to include an order to their worship: but if these words be made to be a distinct period, then that period was only obligatory to the Jews, and to Christians in equal danger, and under the same reason: and therefore can also pass away with the reason, which was but temporary, transient, and accidental; all the rest retaining their prime, natural, and essential obligation.”

The use of images, however, increased as the church increased, though the Council of Eliberis (A.D.305), by its 36th canon, said, “Placuit picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adoratur in parietibus depingatur.” {It was decided that there should not be pictures in the church, so that what is worshiped and adored should not be painted on the walls.} It will be observed that this canon is against painted pictures.

But the struggle against the natural course of events was vain. It was apparent that there was a language to be addressed to the eye as well as the ear, that men might be taught by form and colour as well as by sound, and that many incapable of the latter were capable of the former kind of education.

Gregory the Great wrote to Serenus, Bishop of Marseilles, who had broken images in churches, a letter full of good sense: “Furthermore we notify to you that it has come to our ears that your Fraternity, seeing certain adorers of images, broke and threw down these same images in Churches. And we commend you indeed for your zeal against anything made with hands being an object of adoration; but we signify to you that you ought not to have broken these images. For pictorial representation is made use of in Churches for this reason; that such as are ignorant of letters may at least read by looking at the walls what they cannot read in books. Your Fraternity therefore should have both preserved the images and prohibited the people from adoration of them, to the end that both those who are ignorant of letters might have wherewith to gather a knowledge of the history, and that the people might by no means sin by adoration of a pictorial representation.”

The distinction here taken between the use and abuse of images was one never entirely lost sight of by our Church, though during one period much obscured.

{editor:} Sir Phillimore describes the Nicene council and the reaction of Charlamagne to it. He then moves ahead in history and writes:

But as the Popes became, after the destruction of the Exarchate of Ravenna and the subjugation of the Greek Church, more and more absolute, in this, as in so many other instances, they succeeded in converting an use into an abuse, and in grafting a superstitious innovation upon an innocent and edifying practice of the Catholic Church.

Long before the period when Lyndwood collected and commented upon the constitutions of the English Church, the adoration of images was practiced and enjoined in it; and it is not unimportant, with reference to the construction of the law in England after the Reformation, to consider what was the previous law on this subject.

We learn from Lyndwood that a provincial constitution of Archbishop Winchelsey, which relates to the duties of parishioners as to furnishing certain articles for Divine worship (supellex rei Divinae), orders them to provide certain books, ornaments for the minister and the altar, and, among other things, “imagines in ecclesia, imaginem principalem in cancello…Reparationem navis ecclesiae interius et exterius tam in imaginibus quam in fenestris vitreiis.” {images in the church, the main image on the railing…Repair of the interior and exterior of the nave of the church both in images and in the stained glass windows} […] He says they subserve three purposes: (1.) The instruction of the ignorant; (2.) The reminding men of the Incarnation and of the example of Saints; (3.) The excitement of devotional feeling. He then considers at length the distinction of latria and doulia, and says that the crucifix is “utroque modo veneranda.”6

The subtle distinctions which the Church of Rome endeavored to establish between the latria due to our Lord, the doulia due to the saint, the hyperdoulia due to the Blessed Virgin, even if they had been, as they were not, well founded, were unintelligible to the people, and led to a very gross abuse in the direct worship of the images themselves.

I agree with Mr. Phillpotts, that this abuse fell under the especial censure of those who conducted the Reformation in England, and that they were bent upon the extirpation of it. At the same time, the wiser heads among them well knew what is expressed in our 30th Canon, that “the abuse of a thing doth not take away the use of it,” and that it was “the wisdom of the Church of England” in this matter, as well as in her Liturgy, ‘to keep the mean between the two extremes.’7

Latimer expresses himself as follows:

I said this word ‘saints’ is diversely taken of the vulgar people: images of saints are called saints, and inhabitants of heaven are called saints. Now, by honoring of saints is meant praying to saints. Take honoring so, and images for saints, so saints are not to be honored; that is to say, dead images are not to be prayed unto…and yet I showed the good use of them to be laymen’s books, as they be called; reverently to look upon them, to remember the things that are signified by them, etc. And yet I would not have them so costly and curiously gilded and decked, that the quick image of God (for whom Christ shed his blood, and to whom whatsoever is done, Christ reputeth it done to himself) lack necessaries and be unprovided for by that occasion, for then the laymen doth abuse his book.8

Archbishop Cranmer, in the Book of Articles, which he induced the Convocation of 1536 to pass, says of images:

That they be representers of virtue and good example. That they be stirrers of men’s minds, and make them often to remember and lament their sins, especially the images of Christ and our Lady. That it was meet that they should stand in the churches, but be none otherwise esteemed. That the bishops and preachers diligently teach the people according to this doctrine, lest there might fortune idolatry to ensue. That they be taught also that censing, kneeling, and offering to images be by no means to be done (although the same had entered by devotion and fallen to custom), but only to God and in his honor, though it be done before the images.9

In 1537 The Institution of a Christian Man was published. It had been composed in convocation three years before, under the auspices, it is believed, of Cranmer. It speaks as follows:

Second, that although all images, be they engraven, painted, or wrought in arras,10 or in any otherwise made, be so prohibited that they may neither be bowed down unto nor worshipped (forasmuch as they be the works of man’s hand only), yet they be not so prohibited, but that they may be had and set up in churches, so it be for none other purposes, but only to the intent that we (in beholding and looking upon them, as in certain books, and seeing represented in them the manifold example of virtues which were in the saints, represented by the said images) may the rather be provoked, kindled, and stirred to yield thanks to our Lord, and to praise him in his said saint, and to remember and lament our sins and offenses, and to pray God that we may have grace to follow their goodness and holy living. As for an example: The image of our Savior, as an open book, hangeth on the cross in the rood, or is painted in cloths, walls, or windows, to the intent that beside the examples of virtues which we may learn at Christ, we may also be provoked to remember his painful and cruel passion, and also to consider ourselves, when we behold the said image, and to condemn and abhor our sin, which was the cause of his so cruel death, and thereby to profess that we will no more sin.

In [Richard] Cromwell’s injunctions in the King’s name, there were directions to the clergy “to remove such images as had been superstitiously applied to pilgrimages and offerings, or treated with over-proportioned regard.” Curates were to instruct the people that the use of images was to inform the unlearned in the history of saints, and to refresh their memory.

Leaving the reign of Henry the Eighth, we come to that of Edward the Sixth (1546-47), the ecclesiastical acts of which require careful enumeration and investigation.

In 1547, some of the Homilies, twelve in number, were put forth for the first time; they were chiefly compiled by Archbishop Cranmer; only one of them referred to images and relics, subjects, by the way, usually treated of together at this time. It was the Homily of Good Works. This is its language as to images:

Never had the Jews, in their most blindness, so many pilgrimages unto images, nor used so much kneeling, kissing, and censing of them as hath been used in our time. Sects and feigned religions were neither the fortieth part so many among the Jews, nor more superstitiously and ungodly abused, than of late days they have been among us…keeping in divers places, as it were, marts or markets of merits, being full of their holy relics, images, shrines, and works of overflowing abundance ready to be sold; and all things which they had were called holy – holy cowls, holy girdles, holy pardons, holy beads, holy shoes, holy rules, and all full of holiness. And what thing can be more foolish, more superstitious or ungodly, than that men, women, and children should wear a friar’s coat to deliver them from agues or pestilence? or when they die, or when they be buried, cause it to be cast upon them, and hope thereby to be saved.

…Let us rehearse some other kinds of papistical superstitions and abuses, as of beads, lady psalters, and rosaries, of fifteen O’s of St. Bernard’s verses, of St. Agathe’s letters, of purgatory, of masses satisfactory, of stations and jubilees, of feigned relics, of hallowed beads, bells, bread, water, palms, candles, fire, and such other…11

In the year 1549, injunctions were issued by Edward VI, by virtue of 31 Hen. VIII. c. 8, confirmed by 34 and 35 Hen. VIII. c. 23, the Proclamation Statutes. In these injunctions it is said:12

Besides this, to the intent that all superstition and hypocrisy crept into divers men’s hearts, may vanish away, they shall not set forth or extol any images, relics, or miracles, for any superstition or lucre, nor allure the people by any enticements to the pilgrimage of any saint or image; but reproving the same, they shall teach that all goodness, health, and grace ought to be both asked and looked for only of God, as of the very author of the same, and of none other.

2 Item. That they, the persons above rehearsed, shall make or cause to be made in their churches, and every other cure they have, one sermon every quarter of the year at the least, wherein they shall purely and sincerely declare the word of God; and in the same exhort their hearers to the works of faith, mercy, and charity, specially prescribed and commanded in scripture; and that works devised by men’s fantasies, besides scripture, as wandering to pilgrimages, offering of money, candles, or tapers to relics or images, or kissing and licking of the same, and praying upon beads, or such like superstition, have not only no promise of reward in scripture for doing of them, but contrariwise, great threats and maledictions of God, for that they be things tending to idolatry and superstition, Which of all other offenses God Almighty doth most detest and abhor, for that the same diminish most his honor and glory.

3 Item. That such images as they know in any of their cures to be or have been so abused with pilgrimage or offerings of anything made thereunto, or shall be hereafter censed unto, they (and none other private persons) shall, for the avoiding of that most detestable offense of idolatry, forthwith take down, or cause to be taken down, and destroy the same; and shall suffer from henceforth no torches, nor candles, tapers, or images of wax to be set afore any image or picture, but only two lights upon the high altar, before the sacrament, which for the signification that Christ is the very true light of the world, they shall suffer to remain still, admonishing their parishioners that images serve for no other purpose but to be a remembrance, whereby men may be admonished of the holy lives and conversation of them that the said images do represent; which images if they do abuse for any other intent, they commit idolatry in the same, to the great danger of their souls.”

(11.) Also, if they have hertofore declared to their parishioners anything to the extolling or setting forth of pilgrimages, relics, or images, or lighting of candles, kissing, kneeling, decking of the same images, or any such superstition, they shall now openly, before the same, recant and reprove the same; showing them (as the truth is) that they did the same upon no ground of scripture, but were led and seduced by a common error and abuse, crept into the Church through the sufferance and avarice of such as felt profit by the same.”13

(28.) Also, that they shall take away, utterly extinct, and destroy all shrines, covering of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindles, or rolls of wax, pictures, paintings, and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry, and superstition; so that there remain no memory of the same in walls, glass windows, or elsewhere within their churches or houses. And they shall exhort all their parishioners to do the like within their several houses. And that the churchwardens, at the common charge of the parishoners in every church, shall provide a comely and honest pulpit, to be set in a convenient place within the same, for the preaching of God’s word.14

By this proclamation, having at the time statuable authority, it is clear that only abused images, including pictorial representations in windows and other places, were ordered to be removed.

The next reference is to a document which has been greatly relied upon by the respondent.

On the 24th February 1547, Cranmer sent to the Bishop of London what is called “Mandatum ad amovendas et delendas imagines,” in which, among others, is the following passage:

After our right hardy recommendations to your good lordship; where now of late in the king’s majesties’ visitation, among other godly injunctions commanded to be generally observed through all parts of this his highnesses realm, one was set forth, for the taking down of all such images as had at any time been abused with pilgrimages, offerings or censings; albeit that this said injunction hath in many parts of the realm been well and quietly obeyed and executed, yet in many other places much strife and contention hath risen and daily riseth, and more and more increaseth, about the execution of the same, some men being so superstitious or rather willful as they would by their good wills retain all such images still, although they have been most manifestly abused, and in some places also the image which by the said injunctions were taken down, be now restored and set up again, and almost in every place is contention for images, whether they have been abused or not; and while these men go about on both sides contentiously to obtain their minds, contending whether this or that image hath been offered unto, kissed, censed, or otherwise abused, parties have in some places been taken in such sort, as further inconvenience is very like to ensue if remedy be not provided in time; considering therefore that almost in no places of this realm is any sure quietness, but where all images be wholly taken away and pulled down already, to the intent that all contention in every part of this realm for this matter may be clearly taken away, and that the lively images of Christ should not contend for the dead images, which be things not necessary, and without which the churches of Christ continued most godly many years. We have thought good to signify unto you that his highness’ pleasure with the advice and consent of us the lord protector and the rest of the council is, that immediately upon the sight hereof, with as convenient diligence as you may, you shall not only give order that all the images remaining in any church or chapel within your diocese be removed and taken away, but also by your letters signify unto the rest of the bishops within your province his highness’ pleasure for the like order to be given by them and every of them within their several dioceses; and in the execution thereof we require both you and the rest of the bishops foresaid to use such foresight as the same may be quietly done with as good satisfaction of the people as may be.15

This document, whatever name it is entitled to, orders the removal of “all the images remaining in any church or chapel.”

The injunctions I held in Martin v. Maconochie had legal authority.

But this document is of another kind. It derived no validity from the Supremacy Act, or from the Proclamation Act, for that was repealed before it issued. It is in truth a Latin letter by Cranmer to the Bishop of London, in which he recites an English letter from the Council to him. That English letter is not signed by the King. It indeed purports to be issued by him, with the consent of the Protector and Council, who do sign it; but it is certainly not signed by the King, nor issued with any of the usual formalities; while I observed that a very similar document, called “The King’s order for bringing in Popish Rituals,: in 1549, contains, at the beginning, “By the Kinge,” and at the end, “By the Kinge, inscriptio hoc est.”16 The injunctions are subscribed by the King. Sir John Dodson treated this document, of the 24th February 1547, as of no legal authority. Burnet speaks of it as “a letter.” I do not recollect that in any of the cases in which this document has been discussed, the force of a law was ever ascribed t it, or in any of the subsequent ecclesiastical instruments.It was referred to in the judgment of the Privy Council, but I think it is a misconception to suppose that they decided it to have legal authority. It was introduced as an historical fact, and they considered it in that light. Their Lordships say: “On the 21st of February 1548, N.S., “another proclamation was issued, upon the authority of which it is contended that all images, including crosses, were to be taken down.” They do not say that the contention was founded in law, and they inadvertently call the document a proclamation, which it was not. They afterwards say: “…The intention was not to introduce within the inhibition articles of a description not before forbidden, but to do away with the distinction between images which had been and images which had not been abused.”17 That was undoubtedly the effect of the document, but I do not remember that the legal character of it was ever argued before them. They treat it, I think, as an historical fact. Whatever was its character, it could not, in their opinion, apply to crosses, the legality of which they were considering.

In the same year, but subsequently to this letter, Cranmer issued his Visitation Articles to the diocese of Canterbury, and among them the following:

Item. Whether they have not removed, taken away, and utterly extincted and destroyed in their churches, chapels, and houses, all images, all shrines, coverings of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindles or rolls of wax, pictures, paintings and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry and superstition, so that there remain no memory of the same in walls, glass windows, or elsewhere.18

This is a repetition, almost verbatim, of the twenty-eigth injunction already referred to, except that it is extended of houses, and that the words all images are introduced; but it seems to me that they, like the pictures and the painted windows, must be in the category of monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, and idolatrous superstition. The inquiry is, whether all images of that kind had been removed.

It may be as well to observe here, that in construing the word image, as used in the ancient and modern formularies of our Church, I adopt generally the definition of Dr. Richardson, “anything made, formed, figured, or fashioned, graved, carved, or painted in imitation, likeness, or representation, a semblance or resemblance, picture or copy, a picture, statue, or effigy.”19

It appears with respect to this very Cathedral of Exeter, that in the year 1321 there were payments made pictori pro imaginabus {to the painter for images}, and for a plate whereon to grind his colors.20 I mean to say that the word “image” properly embraces the work of the painter as well as that of the sculptor, though it may occasionally be used in a more limited sense.

The statute 3 & 4 Edward VI. cap. 10, entitled “An Act for the abolishing and putting away of divers books and images,” enacts (sect. 1) “That all books called Antiphoners, Missals, Grailes, Processionals, Manuals, Legends, Pies, Portuasses, Primers in Latin or English, Couchers, Journals, Ordinals, or other books or writings whatsoever heretofore used for service of the Church, written or printed in the English or Latin tongue, other than such as are or shall be set forth by the King’s Majesty, shall be by authority of this present Act clearly and utterly abolished, extinguished, and forbidden for ever to be used or kept in this realm, or elsewhere within any of the King’s dominions.

Sect. 2 enacts, “That if any person or persons, of what estate, degree, or condition soever he, she, or they be, body politic or corporate, that now have or hereafter shall have in his, her, or their custody, any of the books or writings of the sorts aforesaid, or any images of stone, timber, alabaster, or earth, graven, carved, or painted, which heretofore have been taken out of any church or chapel, or yet stand in any church or chapel, and do not before the last day of June next ensuing deface or destroy, or cause to be defaced and destroyed, the same images and every of them, and deliver or cause to be delivered all and every the same books to the mayor, baliff, constable, or churchwardens of the town where such books then shall be, to be by them delivered over openly within three months next following after the said delivery to the archbishop, bishop, chancellor, or commissary of the same diocese, to the intent the said archbishop, bishop, chancellor, or commissary, and every of them, cause them immediately either to be openly burnt or otherwise defaced and destroyed; shall for every such book or books willingly retained in his, her, or their hands or custody, within this realm, or elsewhere within any of the king’s dominions, and not delivered as aforesaid, after the said last day of June, and be thereof lawfully convict, forfeit and lose to the king our sovereign lord, for the first offense xxs. and for the second offense shall forfeit and lose (being thereof lawfully convict) iv li. and for the third offense shall suffer imprisonment at the king’s will.”

Sect. 6 provides, “That this act, or anything therein contained, shall not extend to any image or picture set or graven upon any tomb in any church, chapel, or churchyard, only for a monument of any king, prince, nobleman, or other dead person, which hath not been commonly reputed and taken for a saint, but that such pictures and images may stand and continue in the like manner and form as if this Act had never been had or made; anything in this Act to the contrary in any wise notwithstanding.”

This statute was repealed by 1st Mar. st. 2, c. 2, which statute is repealed by I Jac. I. c. 25, s. 48.

To me the construction of this extraordinary statute is by no means plain.

It should be remarked, in the first place, that there is a letter of Cranmer to the Archdeacon of Canterbury in 1549, in which he recites that he has received letters missive signed by the king, from the king in council, stating that the Book of Common Prayer, being commanded to be used by all persons in the realm, nevertheless “divers unquiet and evil disposed persons since the apprehension of the Duke of Somersett, have noised and bruted abroad that they should have again their old Latin service, their conjured bread and water, with such like vain and superstitious ceremonies, as though the setting forth of the said book had been the only act of the said duke; we therefore…to put away all such vain expectation,…have thought good…to command,” etc., “all antiphoners,” etc., mentioning the same books as are in the statute, to be delivered up.”21 This order is dated the 25th of December, “the third year of our reign,” but it was not issued till the 14th of February 1549. This statute says nothing about images, and is obviously intended to prevent the restoration of the Latin service by the destruction of the Latin office books in every part of the kingdom. The statute mentions both books and images, graven, carved, or painted, including therefore all pictures; but what does it direct with respect to them? That those who have in their custody any such images, which have heretofore been taken out of, or yet stand in any church, shall deface and destroy them, but shall deliver up the books to certain authorities. There is a penalty for not destroying the books, but none for not destroying the images. The object would seem to be to prevent the restoration to the church, at that time, of the same images which had been abused by worship, and which had been, or ought to have been, removed.

The Privy Council in Westerton v. Liddell, said of this statute: “No doubt, however, it implies that to retain them is illegal, but it relates, in their Lordships’ opinion, to the destruction of images already ordered to be removed, but which either had not been removed, or, having been so, were still retained for private veneration and worship…”22

But I doubt very much whether this Act ought to be construed to prohibit the erection of all images, for the future, in all church, a question not discussed before the Privy Council. There are no express words to this effect. I incline to the opinion that it had a temporary purpose in view, namely, to prevent the restoration of the identical images to church which had been, or ought to have been, taken out of them. It was deemed, as the Thirty-eigth Article deems the Homily on the Perils of Idolatry, “necessary for these times.” I do not think this Act was ever referred to in the ecclesiastical documents of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. I have said that it was repealed by Mary, and it was restored by James I. by the repeal of Mary’s Act. But surely it is reasonable to expect that if it contained universal and perpetual prohibitions of images and books, some reference would have been made to it in the reign of Elizabeth; more especially when it is remembered that the Homily “against the Peril of Idolatry,” in the second book, published by authority in 1562, referred to in the Thirty-fifth of the Thirty-nine Articles, and which, in fact, a fervid controversial sermon against the use as well as the abuse of images, should not, unless I have overlooked it, make any reference to the fact that the statute had abolished all images in 1549, and, as it is contended, the Order in Council of 1547.

The letter of Bishop Sandys to Peter Martyr, dated April 1, 1560, and part of which is referred to by the learned Assessor, leads me, on a study of the whole, to a conclusion different from that which he arrived at. Bishop Sandys writes:

We had not long since a controversy respecting images. The Queen’s Majesty considered it not contrary to the Word of God, nay, rather for the advantage of the Church, that the image of Christ, crucified, together with those of the Virgin Mary and St. John, should be placed as heretofore in some conspicuous part of the church, where they might more readily be seen by all the people. Some of us Bishops thought far otherwise, and more especially as all images of every kind were, at our last visitation, not only taken down, but also burnt, and that too by public authority; and because the ignorant and superstitious multitude are in the habit of paying adoration to this idol above all others. As to myself, because I was rather vehement in this matter, and could by no means consent that an occasion of stumbling should be afforded to the Church of Christ, I was very near being deposed from my office, and incurring the displeasure of the Queen. But God, in whose hand are the hearts of kings, gave us tranquility instead of a tempest, and delivered the Church of England from stumbling-blocks of this kind.”23 There is no reference in this letter to the statute of Edward VI. or the letter of Cranmer.

By this construction of the statute at least the most monstrous consequences are avoided. Can it really be the law that any person now possessing, in his private house, or any body, politic or corporate, possessing in their library any one of these books is liable to these penalties; not only all Her Majesty’s Roman Catholic subjects, but all persons, of whatever religion they may be, who have a collection of books of devotion in their private houses? Is every picture, painted on canvas or glass, or carved in stone, for ever forbidden to the Church of England? I hope I am not wrong in having recourse to a construction of the statute which avoids these consequences.

In Queen Elizabeth’s injunctions “concerning both the clergy and laity of this realm,” issued in 1559, the first year of her reign, are the following passages:

III. Item, that they, the parsons above rehearsed, shall preach in their churches and every other cure they have, one sermon every month of the year at least, wherein they shall purely and sincerely declare the word of God, and in the same exhort their hearers to the works of faith, as mercy and charity, specially prescribed and commanded in Scripture; and that the works devised by man’s fantasies, besides Scripture (as wandering of pilgrimages, setting up of candles, praying upon beads, or such like superstition), have not only no promise of reward of Scripture for dong them, but contrariwise great threatenings and maledictions of God, for that they be things tending to idolatry and superstition, which of all other offenses God Almighty doth most detest and abhor, for that the same diminish most his honor and glory.24

XXIII. Also, that they shall take away, utterly extinct, and destroy all shrines, covering of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindalls, rolls of wax, pictures, paintings, and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry, and superstition, so that there remain no memory of the same in walls, glass windows, or elsewhere within their churches and houses.” And in Injunction XXV. , men are exhorted not to bestow their substance upon “the decking of images” and “other like blind devotions.”25

In 1551, Burnet thinks, previously to the last injunctions, certain bishops and divines addressed the Queen against the use of images, citing passages in Deuteronomy, St. John, Tertullian and other writers. In 1560 Bishop Jewell put out his famous challenge to the Papists, defying them to prove, inter alia, “that images were then set up in the church” (that is, in the primitive churches) “to the intent the people might worship them,” using almost the words of St. Stephen, already adverted to, but very remarkable words to have been used in 1560, showing pretty clearly that he who was supposed to be the writer of the Homily on the peril of idolatry did not object on principle to all images in churches, but to images set up to be worshipped.

About the same time the Queen put out a “proclamation against the defacers of monuments in churches.”

Elizabeth. – The Queen’s Majesty understanding that by means of sundry people, partly ignorant, partly malicious or covetous, there hath been of late years spoiled and broken certain ancient monuments, some of metal, some of stone, which were erected up as well in churches as in other public places within this realm, only to show a memory to the posterity of the persons there buried, or that had been benefactors to the buildings or donations of the same churches or public places, and not to nourish any kind of superstition; by which means not only the churches and places remain at this present day spoiled, broken, and ruinated, to the offense of all noble and gentle hearts, and the extinguishing of the honorable and good memory of sundry virtuous and noble persons deceased; but also the true understanding of divers families in this realm (who have descended of the blood of the same persons deceased) is thereby so darkened as the true course of their inheritance may be hereafter interrupted, contrary to justice; besides many other offenses that hereof do ensure, to the slander of such as either gave or had charge in times past, only to deface monuments of idolatry and false feigned images in church and abbey; and therefore, although it be very hard to recover things broken and spoiled, yet both to provide that no such barbarous disorder be hereafter used, and to repair as much of the said monuments as conveniently may be, Her Majesty chargeth and commandeth all manner of persons hereafter to forbear the breaking or defacing of any parcel of any monument, or tomb, or grave, or other inscription and memory of any person deceased, being in any manner of place: or to break any image of kings, princes, or noble estates of this realm, or of any other that have been in times past erected and set up for the only memory of them to their posterity, in common churches, and not for any religious honor, or to break down and deface any image in glass windows in any church without the consent of the ordinary, upon pain that whosoever shall herein be found to offend, to be committed to the next gaol…”26

These orders of the Queen relate to false feigned images; that is, I suppose, images of false saints or false miracles.

The formulary of the Church most relied upon by the respondent was one of the Homilies published in this reign. I think their authority has been much overstated. They are referred to in the 46th, 49th and 80th of our canons; and the Thirty-fifth of our Articles (“Of the Homilies”) says:

The second book of Homilies, the several titles whereof we have joined under this Article, doth contain a godly and wholesome doctrine, and necessary for these times, as doth the former book of Homilies, which were set forth in the time of Edward the Sixth; and therefore we judge them to be read in churches by the ministers, diligently and distinctly, that they may be understanded of the people.

Bishop Burnet, speaking of the Thirty-fifth Article, observes, I think with accuracy:

That by our approbation of the two books of Homilies it is not meant that every passage of scripture or argument that is made us of in them is always convincing; all that we profess about them is, that they contain a godly and wholesome doctrine.

Other writers of eminence have expressed the same opinion.

The Homily against the Peril of Idolatry was directed against the worship of images. It is impossible not to see that it is in reality a strong controversial tract, perhaps “necessary for those times,” but by no means having the force of statutable authority for all its propositions for all times.

The Twenty-second of our Articles of Religion says:

The Romish doctrine concerning purgatory, pardons, worshipping and adoration, as well of images as of relics, and also invocation of saints, is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.

That is undoubtedly the doctrine of our Church. This article, written in 1553, was adopted by authority in 1562. The article of the Council of Trent, which was dated December 4, 1563, “de invocatione, veneratione, et reliquiis sanctorum et sacris imaginibus,” {concerning the invocation, veneration, and relics of saints and sacred images} though it condemns idolatry, orders due honor and worship (venerationem) to be paid to images of our Lord, the Blessed Virgin, and the Saints. The Church of England, holding her middle course, says this worshipping has no warranty in Scripture, immo verbo Dei contradicit {rather, it contradicts the word of God} (according to the Latin version), but in no article does she say that the erecting of all images in churches is repugnant to the Word of God. On the contrary, Bishop Taylor observed that “the wisdom of the church was remarkable in the variety of sentences concerning the permission of images;” that “at first, when they were blended in the dangers and impure mixtures of Gentilism, and men were newly recovered from the snare, and had the relics of a long custom to superstitions and false worshipings, they endured no images but merely civil; but that as the danger ceased, and Christianity prevailed; they found that pictures had a natural use of good concernment to move less knowing people, by the representment and declaration of a story; and then they, knowing themselves permitted to the liberties of Christianity, and the restraints of nature and reason, and not being still weak under prejudice and childish dangers, but fortified by the excellence of a wise religion, took them into lawful uses.”…Soon afterwards he uses these remarkable expressions: “they transcribed a history…into a table, by figures making more lasting impressions than by words and sentences. While the Church stood within these limits she had natural reasons for her warrant, and the custom of several countries, and no precept of Christ to countermand it.”27

These wise observations lead me to the consideration of an argument put forward by the appellants, which deserves especial notice.

It is to this effect, that assuming for the sake of argument the letter of Cranmer to be law, and the statute of Edward not merely to prohibit the replacing or retaining of particular images in churches at a particular period, but to contain a general enactment rendering illegal for the future images in all churches; nevertheless even on this assumption the present structure would not fall under the edge of these prohibitions, inasmuch as it is not in the sense of them, an image or a series of images.

The images contemplated in these prohibitions were detached separate images, which, if immovable, might be kissed, decked with robes and jewels, worshipped; if moveable, carried in procession. These are the class of images of which Barrow speaks in his Exposition of the Decalogue, on the Second Commandment. He censures “affording to them the same expressions of reverence and respect, that we do or can present unto God himself, with great solemnity dedicating such images to them, with huge care and cost, decking them, with great semblance of devotion, saluting them, and casting themselves down before them; carrying them in procession, exposing them to the people, and making long pilgrimages to them.”

But this reredos contains an historical emblematical representation of certain scenes in the history of our redemption, pictures in stone bassi relievi, not of detached figures, but of a particular story. Let me consider this argument; and first, I must express my decided opinion that whether the structure be legal or not, it is in no way distinguishable, having regard either to the principle or to the letter of the prohibitions, from paintings on canvas, or on the wall, or on the windows.

Quite consistently the Homily on the Peril of Idolatry commends Epiphanius, who “rejected not only carved, graven, and molten images, but also painted images out of Christ’s church,” and the bishops who would not allow paintings on cloths or on walls.

It was mainly on this ground that the painted window in St. Margaret’s Church was vehemently, though unsuccessfully, opposed.

The substance of the articles against the churchwardens in that case was “that they had caused to be set up, in defiance of the laws and canons ecclesiastical, a painted glass in the eastern window, over the communion table, whereon is represented by delineation and colors one or more superstitious picture or pictures, and more particularly, the painted image of Christ upon the Cross.”

I do not think that the carved delineations on this reredos are liable to the abuses, the existence of which caused the orders for the removal of images; they are not liable to have candles burnt before them; to be decked with jewels and precious raiment, or to be kissed or worshipped, or treated as workers of false and feigned miracles; I do not think that according to any reasonable probability this stone screen presents any “peril of idolatry” to the frequenters of the church.

I am fortified in this opinion by considerable authority. In The Homily against the Peril of Idolatry, I find it stated that the “Bishop of Nola caused the walls of the temple to be painted with stories taken out of the Old Testament, that the people, beholding and considering those pictures, might the better abstain from too much surfeiting and riot.”…”And these” (says the writer) “were the first paintings in churches that were notable of antiquity. And so by this example came in painting, and afterward images of timber and stone, and other matter, into the churches of Christians. Now, if ye well consider this beginning, men are not so read to worship a picture on a wall, or in a window, as an embossed and gilt image, set with pearl and stone. And a process of a story painted with the gestures and actions of many persons, and commonly the sum of the story written withal, hath another use in it than one dumb idol or image standing by itself. But from learning by painted stories it came by little and little to idolatry.”

I have now to consider the effect of the judgment delivered in the Court of Arches in the year 1684.

It appears that shortly before that time certain parishioners applied for a faculty to put up in painting, as I understand, pictures of the thirteen Apostles in the parish church of Moulton, in the diocese and county of Lincoln, and I think over the Holy Communion Table, abut certainly at the east end. The Surrogate of the Chancellor of Lincoln granted the faculty, but the Chancellor revoked it, and the Bishop, Dr. Thomas Barlow, appears also to have refused his consent. An appeal was prosecuted to the Court of Arches.

As to the Bishop, I learn from Wood that “He was esteemed by those who knew him well to have been a thorough-paced Calvinist, though some of his writings show him to have been a great scholar, profoundly learned both in Divinity and the civil and canon law.”28

He wrote various tracts on “Cases of Conscience,” and among them, A breviate of the case concerning setting up images in the parish church of Moulton. The tract was published contrary to his expressed testamentary wishes, after his death; and the bookseller writes a preface which shows that he clearly misunderstood the proceedings in the Arches; his error appears, as is often the case, to have been perpetuated by copying. It appears again in a paper called the Old Whig, in 1736, and is thence transcribed into a history of the county of Lincoln. Unfortunately at the time of the trial there were no published ecclesiastical reports; but I have been supplied from the records of the Arches Court with a copy of the libel of the appeal, and of the sentence of the Judge. The libel appears to contain, as probably was the case in those days, a summary of the pleadings on both sides in the court below; the case was entitled “Cook and Others v. Tallent.”

Tallent, who was a clergyman, and also a parishoner, objected to the grant of a Faculty “pro erectione sive pictione effigierum apostolorum in ecclesia,” {for erecting or painting portraits of the apostles in the church} and alleged “that, by the book of Homilies, and more especially by the Homilies against the Peril of Idolatry, and also by the injunctions of King Edward the Sixth and Queen Elizabeth, the painting and setting up the apostles’ effigies in any church or chapel is very dangerous in regard they are superstitious, and do tend to idolatry (as by the said homilies and injunctions to which he refers himself) it doth at large appear. Wherefore he prayed the faculty obtained from the said Court might be pronounced null and void, insomuch as doth related to the setting up of the said effigies.”

It was alleged, on the other hand, by the parishioners, “that the setting up of those pictures was out of an honest and pious intention to beautify the said church, and a work commendable and not to be discountenanced, being not at all repugnant to the injunctions of King Edward the Sixth, Queen Elizabeth, or the Homilies of the Church of England, nor monuments of feigned miracles, nor do any ways tend to superstition.” The statute of Edward the Sixth is not referred to…”That the setting up of the said effigies was no ways offensive to them or any of them, saving only one Thomas Scarlett, who did object against the same as superstitious and idolatrous. Licetque insuper allegaveint that by the opinion and judgment of all orthodox divines the paintings of the effigies of the blest apostles in any church or chapel is not idolatrous or superstitious, but do serve only for ornament, and to put people in remembrance of the holy lives and conversations of those they do represent; and that by the injunctions of Edward the Sixth and the ecclesiastical laws of this land, it is required that all persons and vicars and other ecclesiastical persons shall admonish their parishioners that the same do serve for no other end and purpose; and, therefore, since there is no apparent danger of superstition, the effigies of the holy Apostles in the parish church of Moulton aforesaid may and ought to continue as they are now painted, otherwise it may be of dangerous consequence, since that under such pretended fears of superstition and idolatry most of the churches, chapels, colleges, and other pious and religious places in England may be in danger of being pulled down and demolished, and so in all probability the hatred of idolatry would usher in licentious sacrilege.”

It is certainly entitled to the greatest respect at my hands, and must be considered as an important precedent with reference to the case before me, from which it is only distinguishable by the facts:

Lastly, I come to Mr. Phillpotts’ final argument as to the discretion which ought to be exercised. I agree with him, that as to questions of this kind the Ecclesiastical Court has a discretion to exercise. Ornaments and structures which it may be proper, all the circumstances considered, to allow in some cases, it may be improper to allow in others. Much of the decoration of a cathedral may be unsuitable in a parish church. I am urged to exercise this judicial discretion adversely to the erection of the reredos in this case, on the ground of the tendency to adopt the usages of Rome, said to be now prevalent, and on the ground that this structure is an approach to such uses. If there be such a tendency I deeply lament it, but I doubt whether the tendency is to be counteracted in the way proposed. I think there is a great danger of doing unintentionally the work of the Church of Rome by denying the Church of England the innocent aid which the arts of painting and sculpture, within due limits, minister to religion. If the use of all things abused by Rome were taken from our Church, she would be very bare. “It must be confessed,” say our 30th Canon, “that in the process of time the sign of the Cross was greatly abused in the Church of Rome, especially after that corruption of Popery had once possessed it; but the abuse of a thing does not take away the use of it.”

- that the images appear to have been painted and not sculptured;

- and to have been single detached figures, and not, as in the case before me, part of an historical scene, or, as the Homily terms it, “the process of a story.”

“But concerning those our ceremonies,” says Hooker, “which they reckon for most Popish, they are not able to avouch that any of them was otherwise instituted than unto good, yea, so used at the first. It followeth, then, that they all are such as having served to good purpose, were afterwards converted into the contrary. And sith it is not so much as objected against us, that we retain together with them the evil wherewith they have been infected in the Church of Rome, I would demand who they are whom we scandalize, by using harmless thing unto that good end to which they were first instituted.”

The very learned and pious Dr. Donne says: “God, we see, was the first that made images, and he was the first that forbade them. He made them for imitation; He forbade in danger of adoration. For – qualis dementiae est id colere, quod melius est {it is a kind of insanity to worship that which is better} – what a drowsiness, what a laziness, what a cowardliness of the soul is it, to worship that which does but represent a better thing than itself. Worship belongs to the best. Know thou thy distance and thy period, how far to go and where to stop. Dishonor not God by an image in worshipping it, and yet benefit thyself in following it. There is no more danger out of a picture than out of a history, if thou intend no more in either than example.”29

Archbishop Tenison, before his promotion to Canterbury, wrote a treatise on Idolatry, in which he says:

But for the images or pictures of the saints in their former estate on earth; if they be made with discretion; if they be the representations of such whose saintship no wise man calleth into question; if they be designed as their honorable memorials, they who are wise to sobriety do make use of them; and they are permitted in Geneva itself where remain in the choir of the Church of St. Peter, the pictures of the twelve prophets one side, and on the other those of the twelve apostles, all in wood; also the pictures of the Virgin and St. Peter in one of the windows. And we give to such pictures that negative honor which they are worthy of. We value them beyond any images besides that of Christ: we help our memories by them; we forebear all signs of contempt towards them. But worship them we do not, so much as with external positive sign: for if we uncover the head, we do it not to them, but at them, to the honor of God who hath made them so great instruments in the Christian Church; and to subordinate praise of the saints themselves.30

Archbishop Wake, in that part of his answer to the Bishop of Meaux which is called “An answer to the fourth article of Images and Relics,” section 1, “Of the Benefit of Pictures and Images,”31 observes:

(3.) Were the benefits of images never so great, yet you know this is neither that which we dispute with you, nor for which they are set up in your churches. Your Trent Synod expressly defines that due veneration is to be paid to them. Your catechism says that they are to be had not only for instruction but for worship. And this is the point in controversy betwixt us. We retain pictures, and sometimes even images too in our churches for ornament, and (if there be such uses to be made of them) for all the other benefits you have now been mentioning. Only we deny that any service is to be paid to them; or any solemn prayers to be made at their consecration, for any divine virtues, or indeed for any virtues at all, to proceed from them.”

Works Cited

Alford, Henry ed. Works of John Donne, D.D. Vol. V. London: John W. Parker, 1839

Cardwell, Edward. Documentary Annals of the Reformed Church of England. 2 volumes, Oxford: University Press, 1844.

Church of England. Homilies Appointed to be read in Churches. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1840.

Corrie, George Elwes ed. Sermons and Remains of Hugh Latimer, Sometime Bishop of Worcester. Cambridge: The Parker Society, Cambridge University Press, 1845.

Cumming, John ed. Gibson, Edmund. A Preservative Against Popery. Volume III. London: The British Society for Promoting the Religious Principles of the Reformation, 1849.

Fleury, Claude. Histoire ecclesiastique, 20 volumes, Paris, 1691-1720.

Heber, Reginald ed. The Whole Works of the Right Rev. Jeremy Taylor, D.D. Vol. xii of xv, London: Ogle, Duncan, and Co. 37, Paternoster Row, 1822.

Hooker, Richard. Hooker’s Works. Vol. i, 1825.

Lloyd, Charles, ed. Formularies of Faith. Oxford: University Press, 1856.

Lyndwood, William, Provinciale, seu Constitutiones Angliae.

Milman, Henry. History of Latin Christianity. John Murray, 1855.

Perry, Walter. Lawful Church Ornaments. London: Joseph Masters, 1857.

Richardson, Charles. A New Dictionary of the English Language. London: William Pickering, 1839.

Robinson, Hastings, trans. and ed. The Zurich Letters. Cambridge: The University Press, 1846.

Strype, John. Memorials of the Most Reverend Father in God Thomas Cranmer, Sometime Lord Archbishop of Canterbury. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1812.

Tertullian. The Five Books Against Marcion.

Tyton, Francis, ed. Of idolatry: A Discourse. 1678.

Wood, Anthony. Athenae Oxonienses. F.C.& J Rivington, 1813.

- A rerdos is an altar-piece, screen or partition wall. ↩︎

- Fleury, Histoire Ecclesiastique, tom. 2, l.v.p. 54. ↩︎

- Fleury, ibid. ↩︎

- Tertull. Opera, Adversus Marcion, lib. ii. cap. 22. ↩︎

- Rule of Conscience, Rule vi., Bishop Taylor’s Works, vol. xii., Heber’s ed. p. 397. ↩︎

- Lyndwood, 1,3, t.27 pp.251-253. ↩︎

- Preface to Prayer-Book. ↩︎

- Sermons and Remains of Latimer, p.233, ed. Parker Society, 1845 ↩︎

- Strype’s Memorials of Archbishop Cranmer, b.1.c.xi., vol. 1 p. 160 ↩︎

- An arras is “a rich tapestry, typically hung on the walls of a room or used to conceal an alcove.” ↩︎

- Homily of Good Works, third part. ↩︎

- Card. Doc. Ann., vol. i. pp. 6,7. ↩︎

- Ibid. p.10. ↩︎

- Ibid. p.17. ↩︎

- Ibid. p.47. ↩︎

- Card. Doc. Ann. vol. i pp. 85-87. ↩︎

- Westerton v. Liddell, Moor’e Special Report, pp. 168-9. ↩︎

- Cardwell, Doc. Ann., vol. i. p.50. ↩︎

- Dict., tit. Image. ↩︎

- Olver’s Hist. of Exeter Cathedral, p.185. ↩︎

- Card., Doc. Ann., vol. i. p. 85; Perry, Church Ornaments, pp. 56-61. ↩︎

- Moore, Special Report, p. 171. ↩︎

- Zurich Letters, First Series, No. 71, Parker Society Ed., 1842, pp. 73-74. ↩︎

- Card., Doc. Ann., vol.i. pp. 212, 213. ↩︎

- Ibid. p. 221. ↩︎

- Card., Doc. Ann., vol.i. p. 289. ↩︎

- Bishop Taylor’s Tenth Discourse on the Decalogue. ↩︎

- Wood’s Athenae Oxonieneses, vol.iv. 335, ed. Bliss. ↩︎

- Works, vol. v. p. 250, ed. 1839, Sermon cx. ↩︎

- Archbishop Tenison on Idolatry, chap. xii. pt. 2, p. 297. ↩︎

- Gibson’s Preservative against Popery, vol. iii. tit. ix. p. 217. ↩︎