Who can say that Christianity has had the time to translate the totality of its contents into institutions? I have the impression that instead we are still at the beginning stages of Christianity. —Remi Brague

The dominant view of history within American Christianity is that we have fallen from a golden age of knowledge with the early church, and that things progress towards the imminent return of Christ. Postmillennialism, on the other hand, sees an extremely long time ahead of us, and places us in the early church right now. This means that we should grow in knowledge and application of God’s will gradually, perhaps imperceptibly, over the centuries.

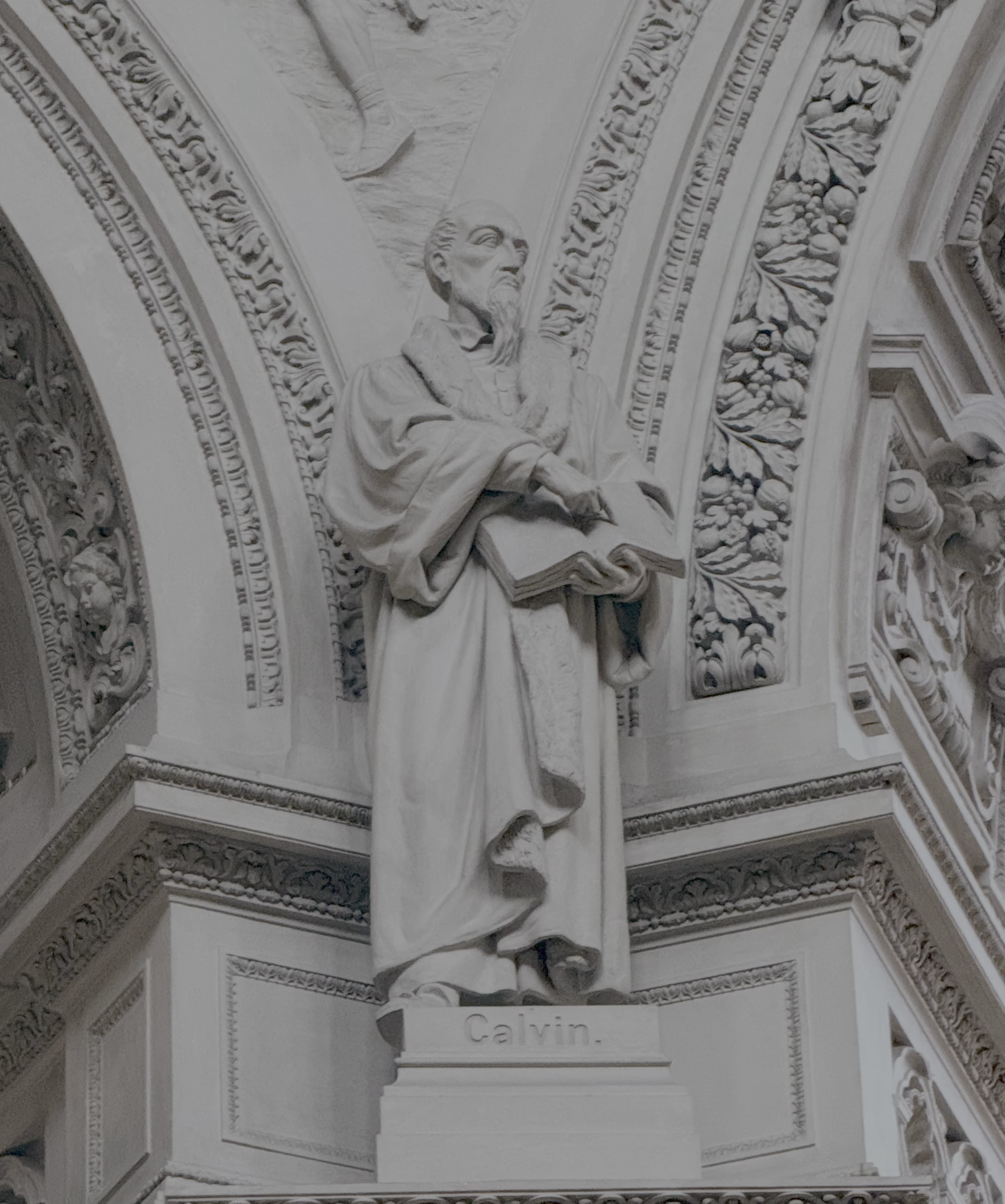

A corollary to this is to see the “Church Fathers” as lacking in knowledge about many Biblical subjects, as opposed to being far more enlightened than we are today. This does not mean that they were not giants of the faith who suffered far more than we ever could, but it does mean that we should not revere anything they thought on any subject due to their antiquity. Calvin is instructive on this point, as William J. Bouwsma points out in his book John Calvin, A Sixteenth Century Portrait:

…basing claims to knowledge on ancient tradition…tended, “to inflate minds with pride and to render them more ferocious.” Antiquity, Calvin insisted, is irrelevant to truth; he ridiculed “counting up the number of ages an error has prevailed,” as an argument in its favor. The ancient fathers, he noted, had sometimes deviated from “the purity and precision of God’s Word through weakness of the flesh or through ignorance…”

Like the ancient sages, the church Fathers were only men, he pointed out; and although they had much of value to say, they were too concerned to come to terms with ancient philosophy and as a result “have left us a cold and dissembling theology.” It is therefore necessary to “decide prudently which among the fathers to imitate,” remembering also that the Lord may, since their time, have “prescribed a different mode of behavior.” Indeed, all the practices of the ancient church must be examined critically. “I do not grant that that age was so free of all defect,” Calvin asserted, “that whatever was done then must be taken as the rule.” He saw Christian antiquity as hardly a more reliable guide for the modern world than pagan antiquity.

Writing in a similar vein, James Jordan said,

The true Fathers of the Church are Noah, Abraham, Joseph, Moses, Jeremiah, Jesus, Paul, Peter, and John, and the other Fathers in the Bible. These men, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, created the apostolic deposit from which the Church always grows.

The men who came after them, in the first and second and third centuries, are not Church Fathers but Church Babies. This is how we should regard Ignatius, Irenaeus, Basil, the Gregories, and yes, even Augustine. I am not saying that in their personal biographies they were spiritual infants; I imagine they were far more mature in Christ than I am. What I am saying is that in terms of the corporate biography of the Church, they lived in the infant stage and their great accomplishments were only the beginning of that corporate biography. We appreciate what the Holy Spirit did with them, and the theological accomplishments they made, but to say that they understood everything and laid everything out definitively would be grotesque, ludicrous, and idiotic.

We may think that because these men lived right after the apostles, they must have known a lot. Remarkably, this is not the case. Anyone who reads the Bible, climaxing in the New Testament, and then turns to the “apostolic fathers” of the second century, is amazed at how little these men seem to have known. The Epistle of Barnabas, for instance, comments on the laws in Leviticus, but completely misinterprets them, following not Paul but the Jewish Letter of Aristeas. It is clear that there is some significant break in continuity between the apostles and these men. What accounts for this? I can only suggest that the harvest of the first-fruit saints in the years before ad 70, which seems to be spoken of in Revelation 14, created this historical discontinuity. (I’d say the first-fruits Church was the Pentecostal harvest of the third month; we look toward the Tabernacles harvest of the seventh month; note Leviticus 23:22, which comes right after the description of the Pentecostal feast, and may well shed significant light on the problem we have here mentioned.)

The Vincentian Canon is no solution to this, as the Fathers manifestly disagreed amongst themselves on a host of basic issues, assuming we haven’t lost vast amounts of literature which would show even more disagreements. John Henry Cardinal Newman recognized this in his An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, where he discussed some of those fundamental problems. He wrote:

It does not seem possible, then, to avoid the conclusion that, whatever be the proper key for harmonizing the records and documents of the early and later Church, and true as the dictum of Vincentius must be considered in the abstract, and possible as its application might be in his own age, when he might almost ask the primitive centuries for their testimony, it is hardly available now, or effective of any satisfactory result. The solution it offers is as difficult as the original problem.

Leave a Reply